Rooted in Clay

By Connie

Matisse

By Connie

Matisse

East Fork’s got a pretty distinct story of origin that sits close at the heart of the team that founded it but somehow, as years pass, gets harder to sum up in words.

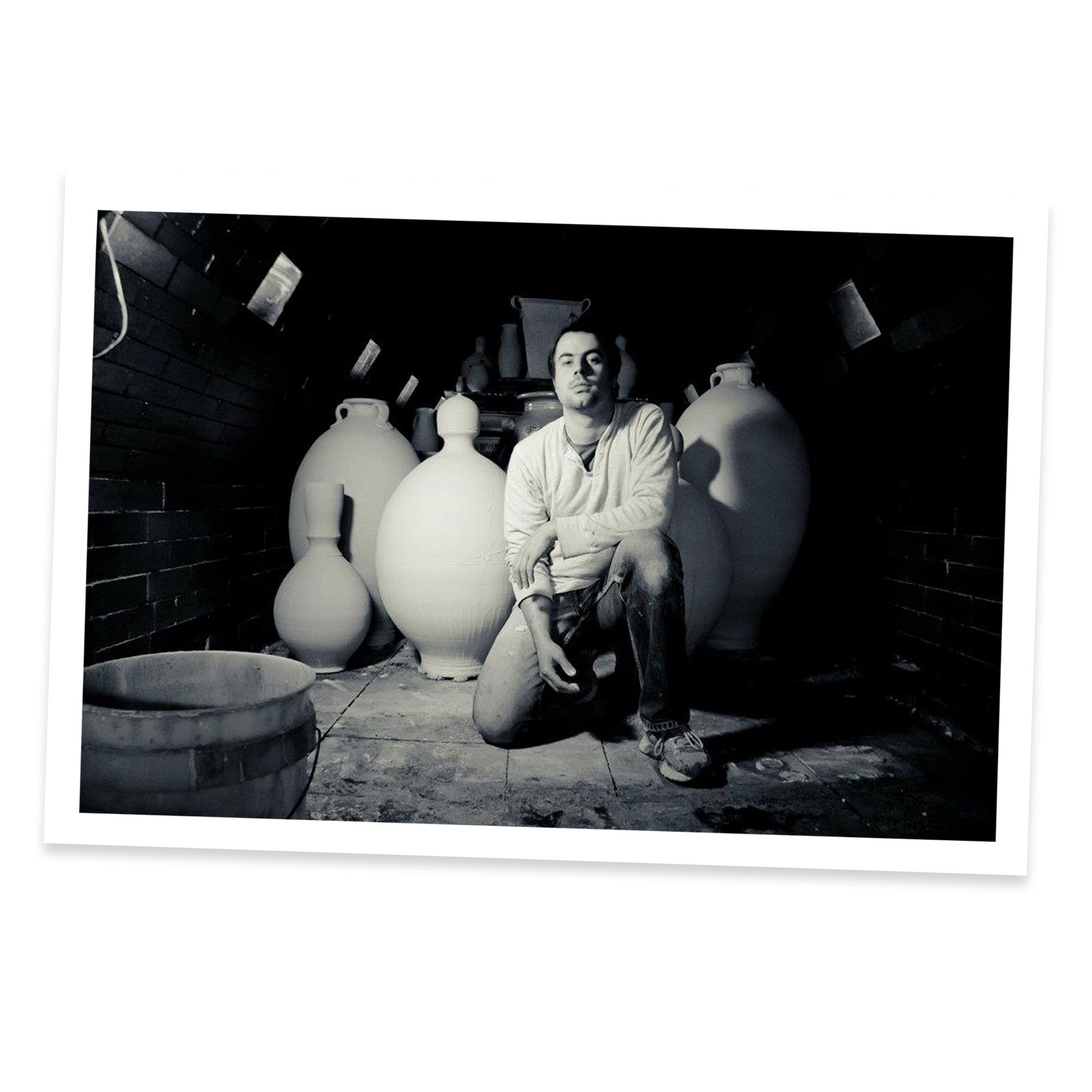

Twelve years into this and I must have written six hundred paragraphs all sharing pretty much the same story in different words and different tones: that Alex Matisse, my husband and East Fork’s Founder—had an early love for clay. That as a child he made clay masks with sunken-in eyes and droopy mouths, full of pain and torment. That he left the Northeast at eighteen, where he’d been raised by a family of artists and anthropologists, and came to North Carolina where his introduction to a centuries-old ceramic tradition and way of making pots gripped him tight in the chest and didn’t let go.

If you’ve been a customer for a while already you’ve probably heard me say that he and our business partner and CFO, John Vigeland, both studied under master North Carolina potters where they learned their scales, so to speak, making runs of dozens and even hundreds of the same form, each one striving toward some hard-to-define ideal—a pleasant rounding on the lip, a perky foot, walls elegant, even, and sturdy.

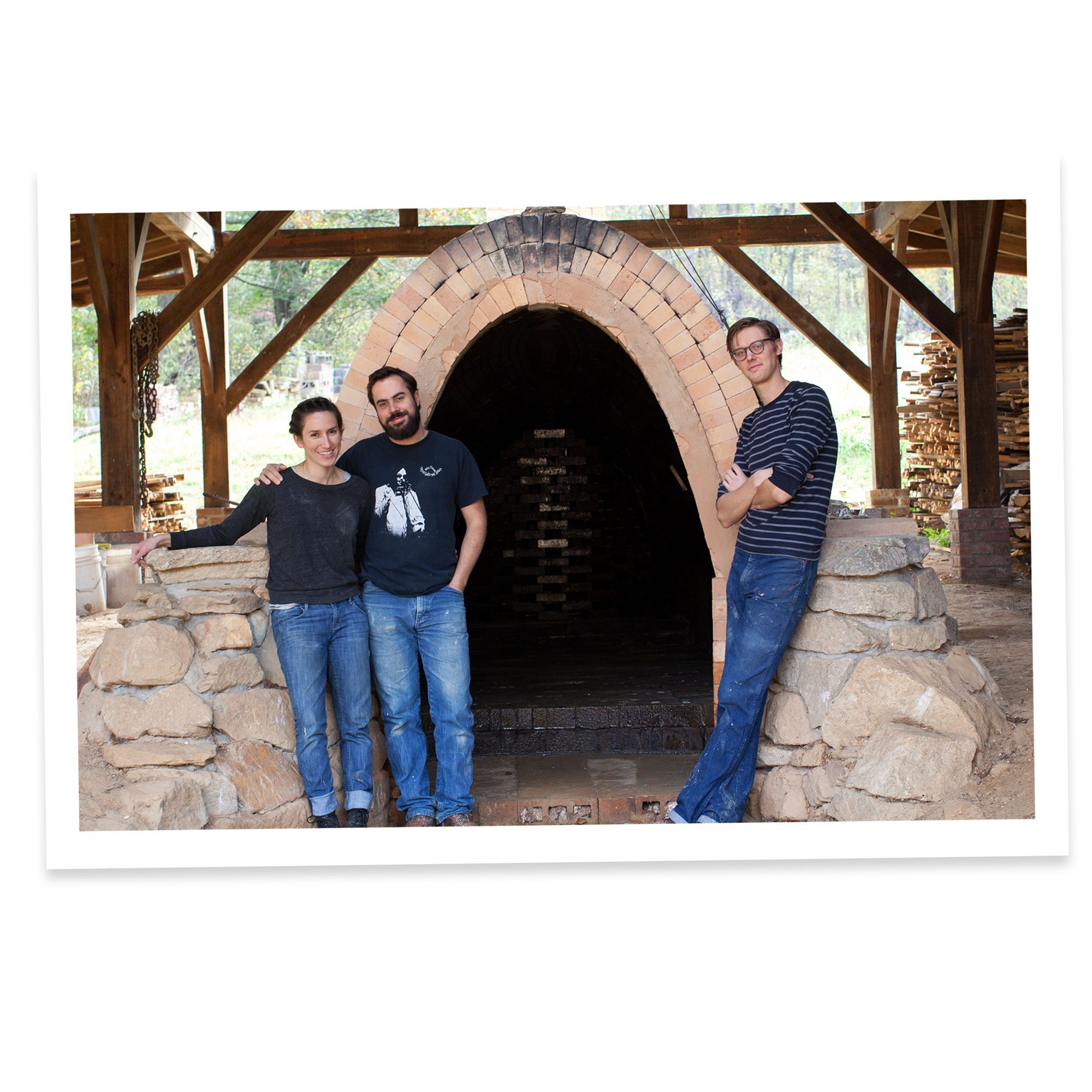

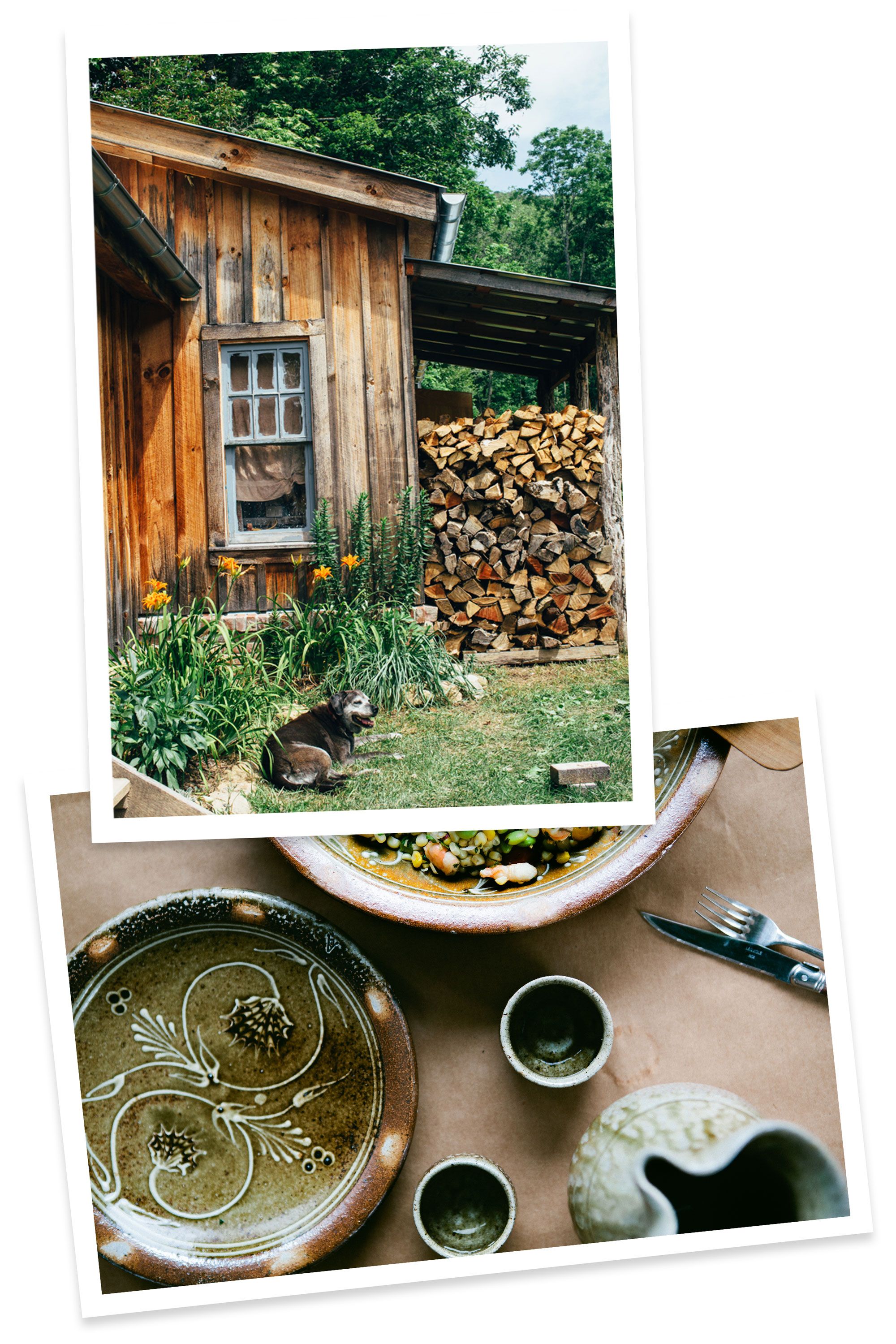

In 2009 Alex left the Mark Hewitt Pottery and bought an old tobacco farm hidden at the end of a dark holler in the mountains just north of Asheville, North Carolina. I met him just after that—I was 24, aimless, a little feral, working on a dairy farm on Tennessee border—and all that first winter and spring he told me about the wood-burning kiln he’d build from bricks, and drew pictures of the workshops he’d put up, with dirt floors and handmade ware racks, and his eyes got big when he described the pots he’d make and about this ravenous group of pottery collectors who’d show up right there in our backyard ready to load up their cars with jars and rundlets and pitchers and bowls.

And it all did happen, just like that.

From 2009 until 2015 East Fork was just Alex and John and a couple of apprentices and early team members making and selling wood-fired pottery in a Southern folk vernacular at twice-yearly kiln sales and crafts shows across the state, with me sticking my camera across everyone’s wheel and posting about what we were up to on social media.

East Fork is really different now than it was back then. On sloggy days, when running the business feels so hard, it’s easy to look back at that time of lunch under the blossoming apple trees and the smell of the damp dirt floor with nostalgia and weepy romance. But the choice to leave that East Fork behind was exactly that—a choice we made to close that chapter to start a new one.