Reviving Hnähñu

Ma Hñäkihu is fiscally sponsored by Colaborativa La Milpa, a 501-(c3) tax exempt organization. You can make a tax deductible donation by visiting this link. To learn more and stay connected with Ma Hñäkihu, please visit their website, mahnakihu.org

How it Started

Abel Bueno Gonzales remembers that the idea for Ma Hñäkihu, an organization to preserve his native, Indigenous language, Hnähñu, was born at about the same time as his son.

Up until that time, Abel, who is Indigenous to the Mezquital Valley in Mexico and who has lived in Buncombe County, NC for more than 20 years, hadn’t spoken Hnähñu since leaving his hometown. Not with his brother, who lives close by or on phone calls with his family. His partner, Andrea Golden, was surprised to learn that he spoke an ancient language after they had been together for some time.

“She told me, you should speak your language more,” Abel says. “That languages are dying out really fast.”

Indeed. According to the United Nations Forum on Indigenous Issues, more than half of the world’s Indigenous languages will disappear this century, as will their “extensive and complex systems of knowledge.”

So, where does one begin? For Abel and Andrea, it began with naming their son a traditional Hnähñu name, Hyadi, which means “sun,” even as Abel was worried that it would provoke the teasing and shame that he had experienced as a child.

Abel had spoken Hnähñu with his grandmother. If he brought this to school, there were classmates who teased him. Some were from families who no longer spoke the language after experiencing shame and discrimination for generations as colonized people whose native language was once illegal.

Graciela Perez, who is a program lead with Ma Hñäkihu, also grew up in the Mezquital Valley. Her mother had been sent to an orphanage to learn Spanish and get a more advanced education. She only spoke Spanish to her children (and still does). Graciela learned Hnähñu from other family members and her community. When she went to school, other children made fun of her Spanish pronunciation. “And the teachers always told us: “You have to speak correctly,” Graciela says.

Abel and his Hnähñu friend, Gregorio “Goyo” Ortiz, found this to be common with their neighbors in Buncombe County when they officially decided to start the Ma Hñäkihu Language Preservation project in 2018 as part of Colaborativa La Milpa (La Milpa), a non-profit collective. They went door-to-door in their community to identify Hnähñu families and heard familiar stories of intergenerational trauma related to speaking Hnähñu and engaging in traditional cultural practices.

Overcoming Shame

Abel and Goyo knew that they would have to break down this shame by teaching the language in healthy ways and providing celebratory spaces and programs where all could feel confident and proud about their identity.

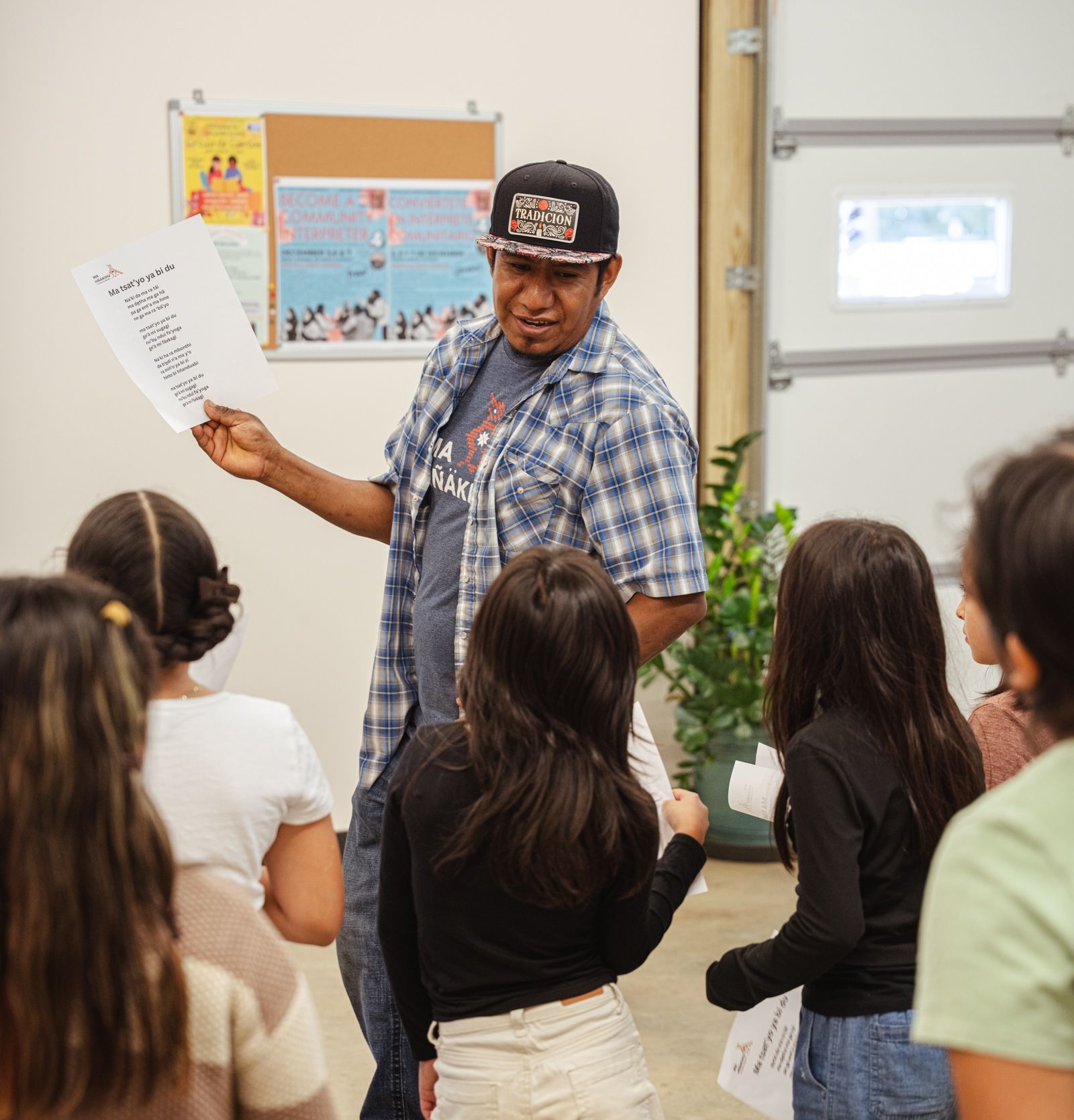

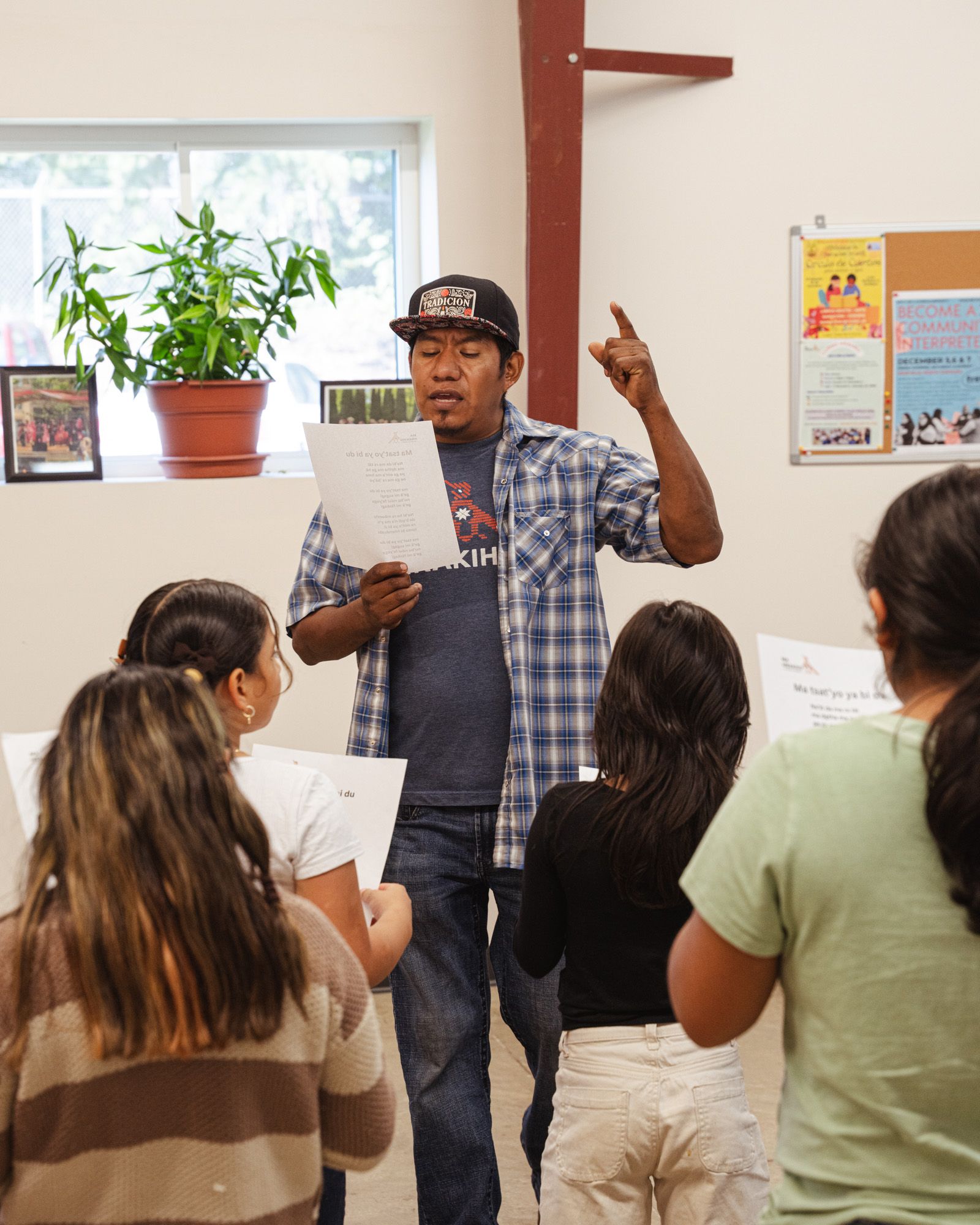

They started classes virtually with Thübini Mästo̲ho̲, a professor of Indigenous languages based in Mexico City, to learn more Hnähñu and how to teach a language. They curated a small Hnähñu library. Hnähñu neighbors were invited to language circles and workshops, and language videos were posted online. Abel and Goyo visited the local community preschool and the summer camp and afterschool programs of Raices, also a member of the La Milpa collective. There, they connected children to Hnähñu through play and art, eventually creating and publishing a Hnähñu curriculum.

Celebrating Identity

In 2021, Ma Hñäkihu sponsored the first annual “Celebrating Our Cultures” Indigenous festival, important for recognition as Indigenous both individually and as a community, which is a deep value of the organization. Another is humility, which is key during classes when students might say, "That's not how you say it. In my place, it's said like this." Abel and Graciela recognize and respect the varied experience their participants have.

“Ma Hñäkihu is my culture,” says Alfonso Alvarado. “It has helped me reconnect with myself and better recognize my identity.”

In 2023, when Graciela came on board, she proposed a Hnähñu dance group to Abel because she hoped to connect more people with the work. At first, adults came to dance and then started to remember or become more interested in the language. Now, they might ask how to say something in Hnähñu or how to pronounce a word. “It’s a very slow process,” Graciela laughs. She understands because when she first came to the United States she was only focused on work. She lost her connection to her language and culture. “And now, when I speak Hnähñu, I feel like I'm returning to the reality that I am.”

“This is a good space, it is very good,” says Josefina Pantoja, a member of the dance group. “It's beautiful to be among the people.”

“Ma Hñäkihu has helped me reconnect with the language since my grandmother spoke it, my father speaks it,” says dancer Miguel Angel.

Ma Hñäkihu Today

Ma Hñäkihu’s programming continues to grow. Annually, they offer 24 language workshops, 22 dance group practices, 15 music and song practices with adults and children and 26 language videos on social media. In 2024, they hosted Hnähñu cultural bearers and artists from Hidalgo, Mexico who offered seminars and workshops in history, craft and dance over 10 days and performed at the annual festival for an audience of approximately 400. Attendance was just as strong at the 2025 Festival, with an introduction of a new Ma Hñäkihu children’s choir.

For the Dias de los Muertos celebration in early November of this year, community members of all ages were invited to learn about and participate in a Xantolo festival dance, whether they were of Hnähñu descent or not. Xantolo is a sacred festival in the Huestaco region of Mexico, combining Indigenous and Catholic traditions and connecting people to the loved ones they’ve lost.

Abel and Graciela are especially excited about their recent work with youth. Of course, Abel says, they are asked, “Why should I reconnect with this language or learn it if I don’t need it here in the United States?” Abel explains to them that they aren’t inviting them to learn because of a need to speak Hnähñu or because that person or their family is from the Mezquital Valley. “I tell them it's important to how you identify yourself and how people identify you,” Abel says. ”Your identity is what matters.”

For Abel’s son, Hyadi, now 11, learning Hnähñu is about his roots. “It helps me understand and learn where my grandparents and parents are from,” he says.

According to Abel, the connection of all the participants in their ongoing programs and the festival is so important because that’s where culture is being revitalized. The community is stronger together, and the community has more faith in its future.

When he and his brother hang out these days, they speak in Hnähñu, and when Abel calls his family, they do, too. It’s been a long and precious journey for Abel’s local community and for him. “When I speak my language,” he says. “I feel free, I feel complete.”